05 - Software Design

ucla | CS 130 | 2024-10-22

Table of Contents

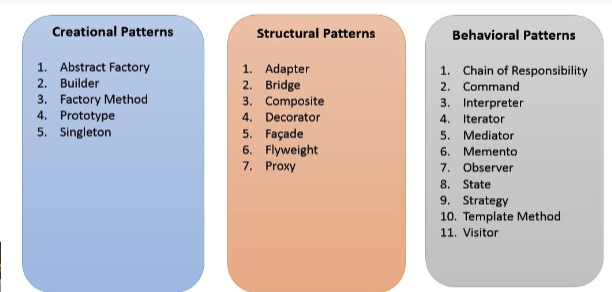

- SOLID Principles

- Gang of Four Design Patterns

- GoF Creational Patterns

- GoF Structural Patterns

- GoF Behavioral Patterns

SOLID Principles

- Single Responsibility Principle

- a class should have responsibility over only a single part of functionality

- Open-Close Principle

- entities should be open for extension but closed for modification

- Liskov Substitution Principle

- subtypes should be substitutable for their supertypes without conflicts

- this allows subtypes to interface with their supertypes and implement/invoke functionality of their supertype(s)

- Interface Segregation Principle

- clients/entities/classes should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use/require

- a violation of this principle would require inheriting types to implement the interface they inherit without ever requiring their implementations

- Dependency Inversion Principle

- pro: design patterns offer common solutions to common problems through common vocabulary

- pro: they reduce system complexity through abstraction and inheritance allowing for better reorganization and refactoring of hierarchies

- pro: allow for flexible and maintainable systems

- con: design patterns have tradeoffs and may be realized differently depending on the codebase and language

- con: directory structure and class naming may reduce readability when adhering to specific design patterns

Gang of Four Design Patterns

GoF Creational Patterns

Factory Method Pattern

The Factory Method design pattern is a creational design pattern that provides an interface for creating objects in a superclass but allows subclasses to alter the type of objects that will be created. This pattern is particularly useful when the exact type of the object to be created isn’t known until runtime or when the creation process involves complex logic.

Concepts

Product: This is the interface or abstract class that defines the type of object the factory method will create.

Concrete Product: These are the specific implementations of the Product interface.

Creator: This is the abstract class or interface that declares the factory method. It may also provide some default implementation.

Concrete Creator: These are the subclasses of the Creator that implement the factory method to return an instance of a Concrete Product.

Structure

- Product Interface: Defines the interface for objects created by the factory method.

- Concrete Products: Implement the Product interface.

- Creator Interface: Declares the factory method.

- Concrete Creators: Implement the factory method to return an instance of a Concrete Product.

Example

Imagine a scenario where you have different types of vehicles (e.g., Car, Truck). You want to create a factory that can produce these vehicles based on some input.

# Product Interface

class Vehicle:

def drive(self):

pass

# Concrete Products

class Car(Vehicle):

def drive(self):

return "Driving a car"

class Truck(Vehicle):

def drive(self):

return "Driving a truck"

# Creator Interface

class VehicleFactory:

def create_vehicle(self):

pass

# Concrete Creators

class CarFactory(VehicleFactory):

def create_vehicle(self):

return Car()

class TruckFactory(VehicleFactory):

def create_vehicle(self):

return Truck()

# Client Code

def get_vehicle(factory: VehicleFactory):

vehicle = factory.create_vehicle()

print(vehicle.drive())

# Usage

car_factory = CarFactory()

get_vehicle(car_factory) # Output: Driving a car

truck_factory = TruckFactory()

get_vehicle(truck_factory) # Output: Driving a truck

Advantages:

- Encapsulation of Object Creation: The creation logic is encapsulated in the factory, making it easier to manage and modify.

- Decoupling: The client code is decoupled from the concrete classes, allowing for easier maintenance and scalability.

- Flexibility: New types of products can be introduced without changing the existing code.

Disadvantages:

- Complexity: It can introduce additional classes and complexity to the codebase.

- Overhead: If not used judiciously, it may lead to unnecessary abstraction.

Abstract Factory Pattern

The Abstract Factory design pattern is another creational design pattern that provides an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes. It is particularly useful when a system needs to be independent of how its objects are created, composed, and represented.

Key Concepts:

Abstract Factory: This is an interface that declares methods for creating abstract products.

Concrete Factories: These are implementations of the Abstract Factory that create specific products.

Abstract Products: These are interfaces or abstract classes that define the types of objects that can be created.

Concrete Products: These are the specific implementations of the abstract products.

Structure:

- Abstract Factory: Declares methods for creating abstract products.

- Concrete Factories: Implement the abstract factory methods to produce concrete products.

- Abstract Products: Define the interfaces for a family of products.

- Concrete Products: Implement the abstract product interfaces.

Example:

Consider a scenario where you want to create different types of user interfaces for different operating systems (e.g., Windows and macOS). Each operating system has its own set of UI components (buttons, checkboxes, etc.).

# Abstract Products

class Button:

def paint(self):

pass

class Checkbox:

def paint(self):

pass

# Concrete Products for Windows

class WindowsButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return "Rendering a Windows button"

class WindowsCheckbox(Checkbox):

def paint(self):

return "Rendering a Windows checkbox"

# Concrete Products for macOS

class MacOSButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return "Rendering a macOS button"

class MacOSCheckbox(Checkbox):

def paint(self):

return "Rendering a macOS checkbox"

# Abstract Factory

class GUIFactory:

def create_button(self):

pass

def create_checkbox(self):

pass

# Concrete Factories

class WindowsFactory(GUIFactory):

def create_button(self):

return WindowsButton()

def create_checkbox(self):

return WindowsCheckbox()

class MacOSFactory(GUIFactory):

def create_button(self):

return MacOSButton()

def create_checkbox(self):

return MacOSCheckbox()

# Client Code

def client_code(factory: GUIFactory):

button = factory.create_button()

checkbox = factory.create_checkbox()

print(button.paint())

print(checkbox.paint())

# Usage

windows_factory = WindowsFactory()

client_code(windows_factory)

# Output:

# Rendering a Windows button

# Rendering a Windows checkbox

macos_factory = MacOSFactory()

client_code(macos_factory)

# Output:

# Rendering a macOS button

# Rendering a macOS checkbox

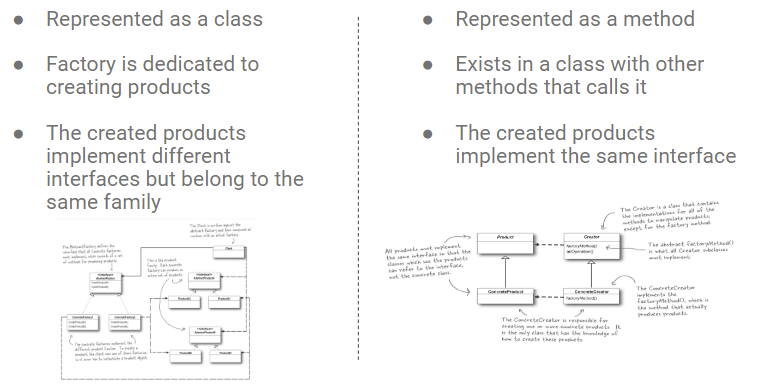

Differences from Factory Method:

- Purpose:

- Factory Method: Focuses on creating a single product or a family of related products. It allows subclasses to alter the type of objects that will be created.

- Abstract Factory: Focuses on creating families of related or dependent objects. It provides an interface for creating multiple products that are designed to work together.

- Structure:

- Factory Method: Typically involves a single method for creating a product. It can be seen as a single factory for one type of product.

- Abstract Factory: Involves multiple methods for creating different types of products. It can be seen as a factory for multiple related products.

- Use Cases:

- Factory Method: Used when a class cannot anticipate the class of objects it must create or when subclasses need to specify the objects they create.

- Abstract Factory: Used when a system needs to be independent of how its products are created, composed, and represented, especially when dealing with multiple families of products.

TLDR:

In summary, while both the Factory Method and Abstract Factory patterns deal with object creation, the Factory Method is focused on creating a single product, whereas the Abstract Factory is concerned with creating families of related products. The Abstract Factory pattern provides a higher level of abstraction and is useful in scenarios where multiple products need to be created that are designed to work together.

Abstract Factory vs Factory Method

Singleton Pattern

The Singleton design pattern is a creational pattern that ensures a class has only one instance and provides a global point of access to that instance. This pattern is particularly useful when exactly one object is needed to coordinate actions across the system, such as in cases of configuration management, logging, or managing shared resources.

Key Concepts:

Single Instance: The Singleton pattern restricts the instantiation of a class to a single object. This is typically achieved by making the class constructor private or protected.

Global Access Point: The Singleton class provides a static method that allows clients to access the instance. This method is responsible for creating the instance if it does not already exist.

Lazy Initialization: The instance is created only when it is needed, which can help with resource management.

Structure:

- Singleton Class: Contains a private static variable to hold the single instance and a private constructor to prevent instantiation from outside the class. It provides a public static method to access the instance.

Example:

Here’s a simple implementation of the Singleton pattern in Python:

class Singleton:

_instance = None

def __new__(cls):

if cls._instance is None:

cls._instance = super(Singleton, cls).__new__(cls)

# Initialize any attributes here if needed

return cls._instance

def some_business_logic(self):

# Example method to demonstrate functionality

return "Doing some business logic"

# Client Code

singleton1 = Singleton()

singleton2 = Singleton()

print(singleton1 is singleton2) # Output: True, both variables point to the same instance

# Using the singleton instance

print(singleton1.some_business_logic()) # Output: Doing some business logic

Advantages:

Controlled Access: The Singleton pattern provides controlled access to the single instance, ensuring that no other instances can be created.

Global Access: It provides a global point of access to the instance, making it easy to use throughout the application.

Lazy Initialization: The instance is created only when it is needed, which can help save resources.

Disadvantages:

Global State: Singletons can introduce global state into an application, which can make testing and debugging more difficult.

Concurrency Issues: In multi-threaded environments, care must be taken to ensure that the Singleton instance is created safely, as multiple threads may attempt to create an instance simultaneously.

Hidden Dependencies: The use of Singletons can lead to hidden dependencies in the code, making it harder to understand and maintain.

Variants:

Thread-Safe Singleton: In multi-threaded applications, you may need to implement additional mechanisms (like locks) to ensure that the Singleton instance is created safely.

Eager Initialization: Instead of lazy initialization, the instance can be created at the time of class loading.

Bill Pugh Singleton: This approach uses a static inner helper class to hold the Singleton instance, which is only loaded when the

getInstance()method is called.

TLDR:

The Singleton pattern is a useful design pattern when you need to ensure that a class has only one instance and provide a global point of access to it. While it offers several advantages, such as controlled access and lazy initialization, it also comes with potential drawbacks, particularly in terms of global state and testing challenges. Careful consideration should be given to its use in software design.

GoF Structural Patterns

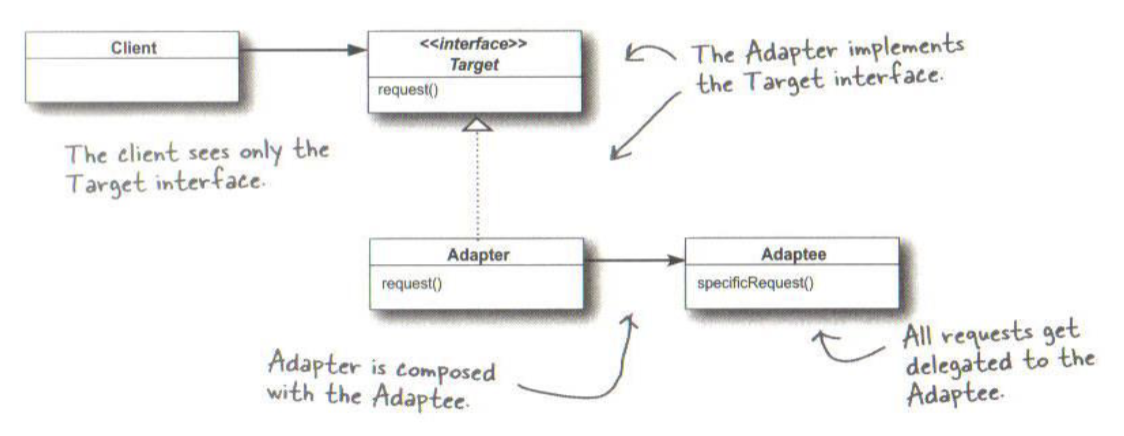

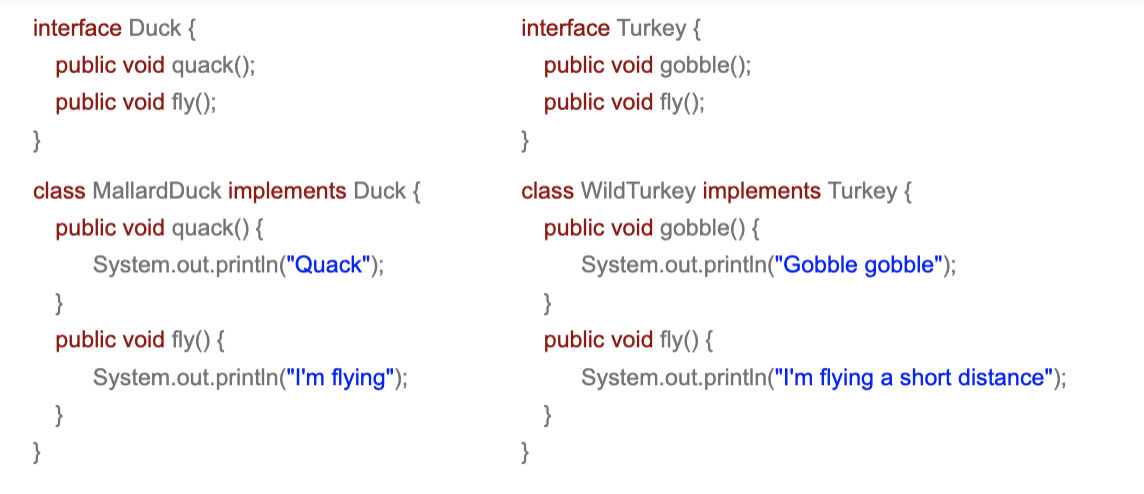

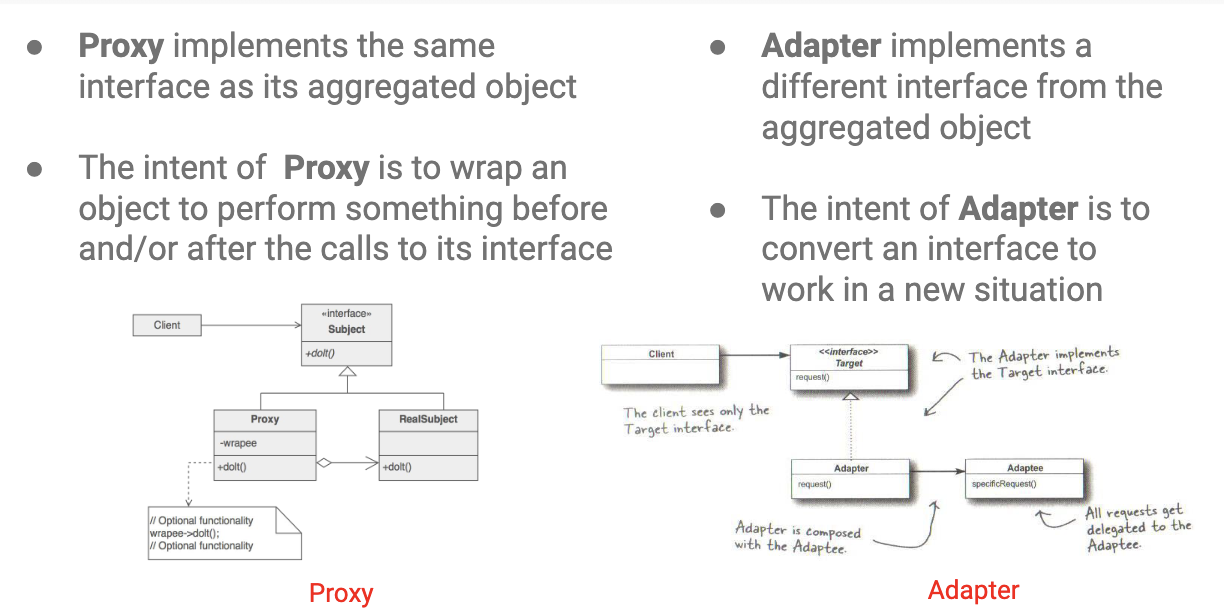

Adapter Pattern

- implemented to adapt an existing component to a new interface/system

- adapters extend/implement the interface/class so, depending on lang, they MUST implement all functionality of the interfaces they extend

Java Example

- existing

- adapted

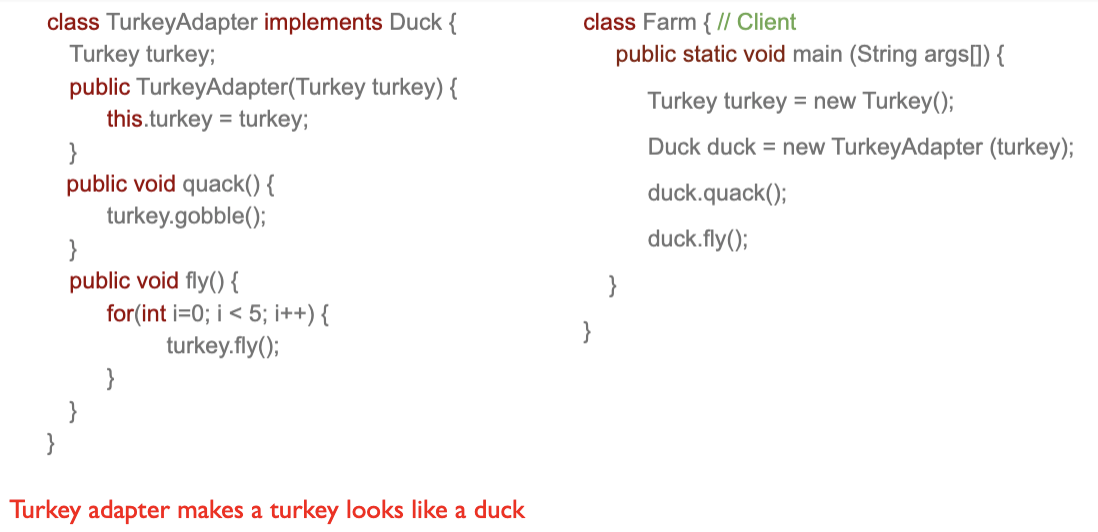

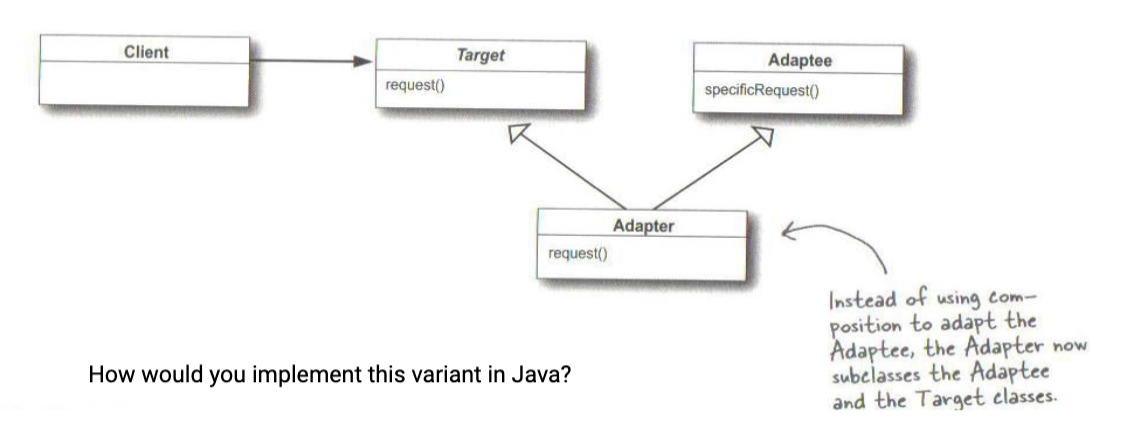

Adapter Variant

- multiple inheritance, e.g. multi-interface implementation

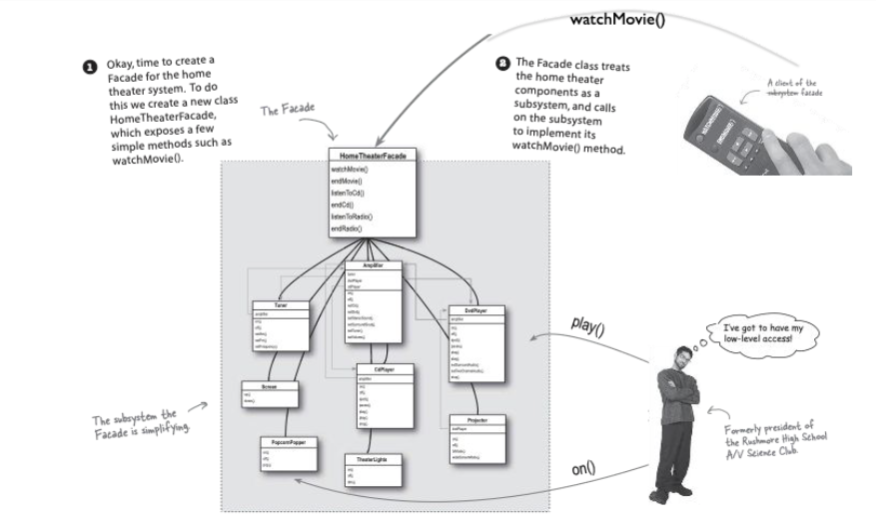

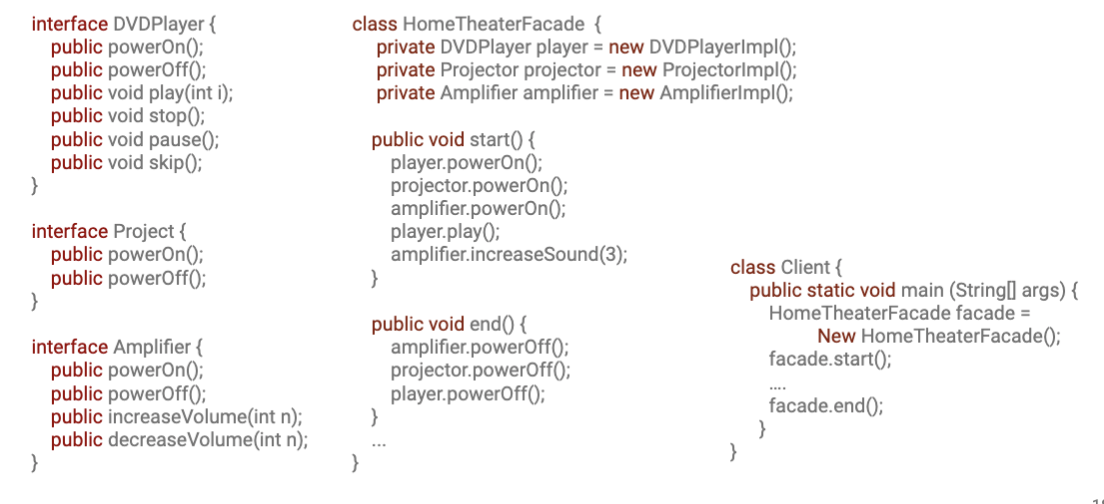

Facade Pattern

- given a complex system (complex interrelation of classes and methods), implement a Facade to simplify the interface to the complex system

Java example

- facade simplifies multi-class interconnections

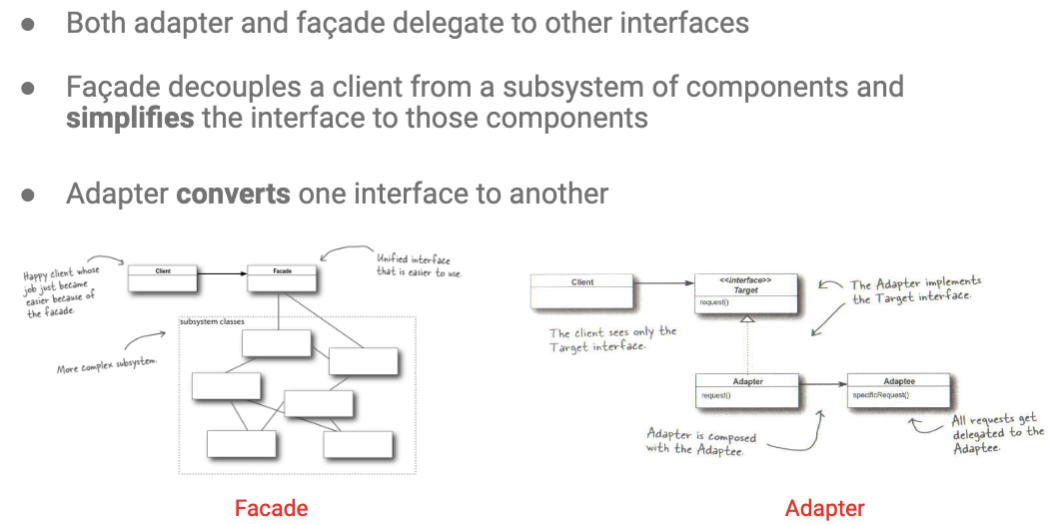

Facade vs Adapter

- facades associate objects as attributes -> this allows them to not have to implement all functionality of the interface/object/class

- facade focuses on simplification while adapters perform interface “conversion”

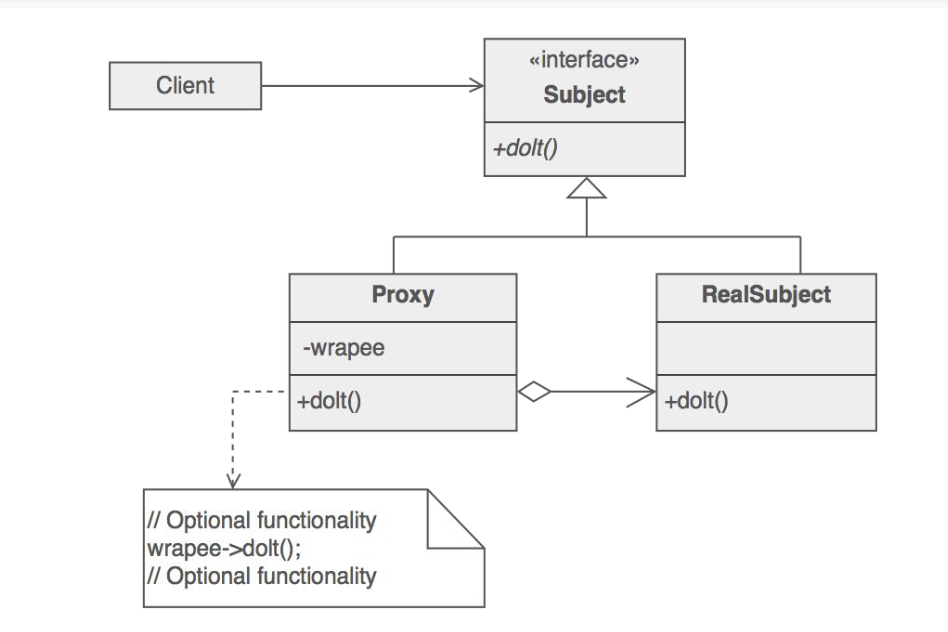

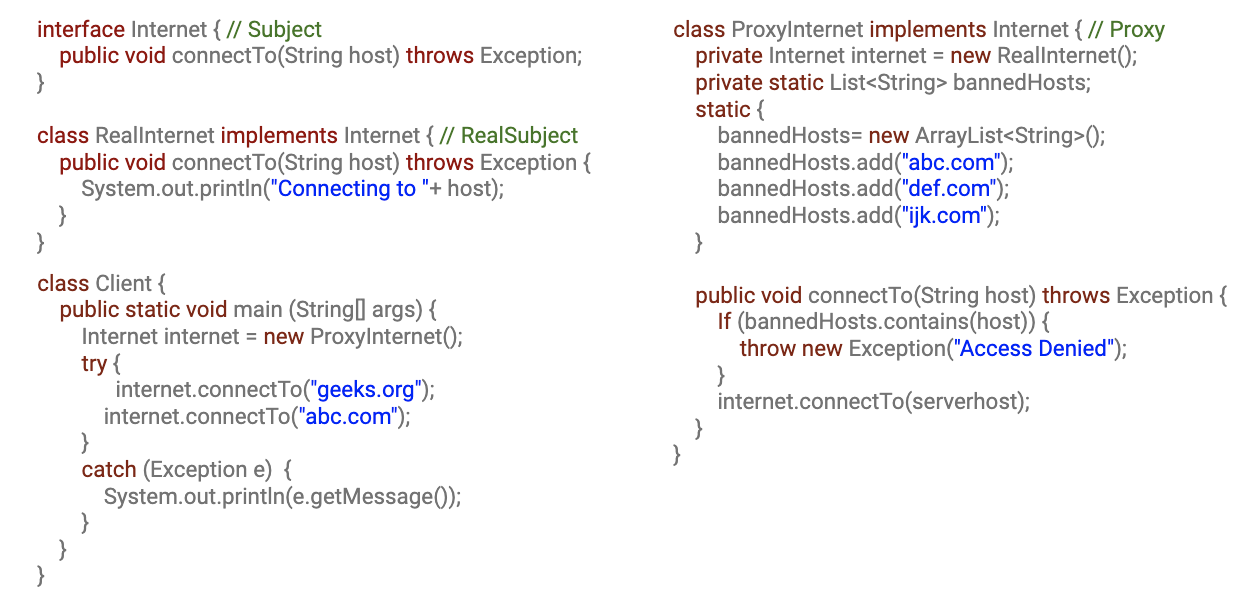

Proxy Pattern

- limits access to an object by requiring interfacing through middleware (a proxy)

- Virtual proxy - can be a placeholder for expensive to create objects. The real object is only created when a client first requests/accesses the object.

- Remote proxy - provides a local representative for an object that resides in a different address space. This is what “stub” code in remote-procedure-calls (RPC) provides.

- Protective proxy - controls access to a sensitive master object. The surrogate object checks that the caller has the access permissions required prior to forwarding the request.

- Smart proxy - adds additional actions when an object is accessed. Typical uses include:

- proxy internet to act as a firewall

- proxies implement/extend the interface so, depending on the lang, they MUST implement all functionality of the interface

Proxy vs Adapter vs Facade

- proxy vs facade - facades don’t implement/extend

- proxy vs adapter - proxy and the real subject extend the same interface while in an adapter, the adaptee does not extend the target

- proxies could be implemented as decorators/wrappers

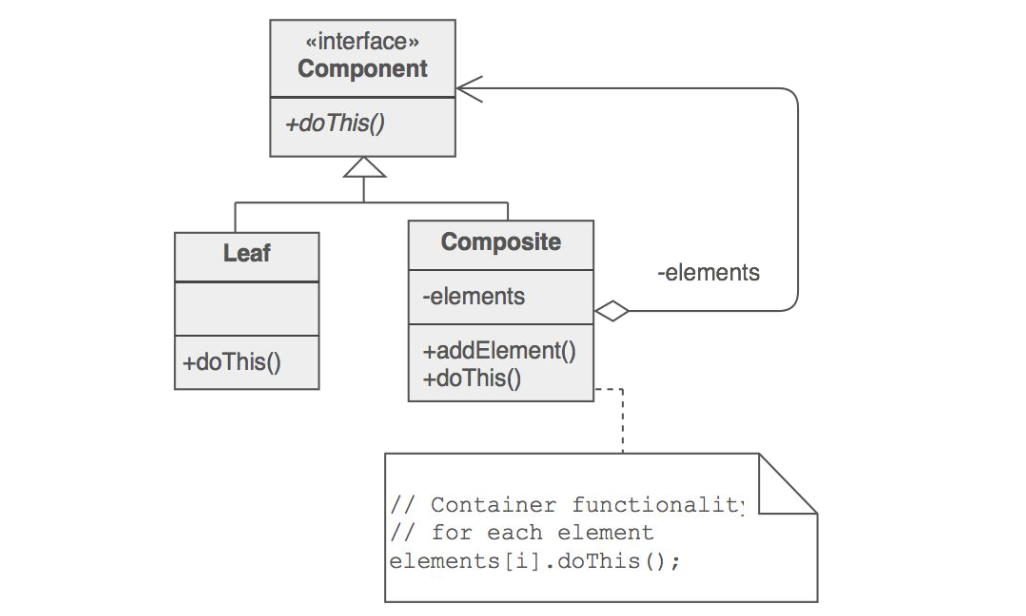

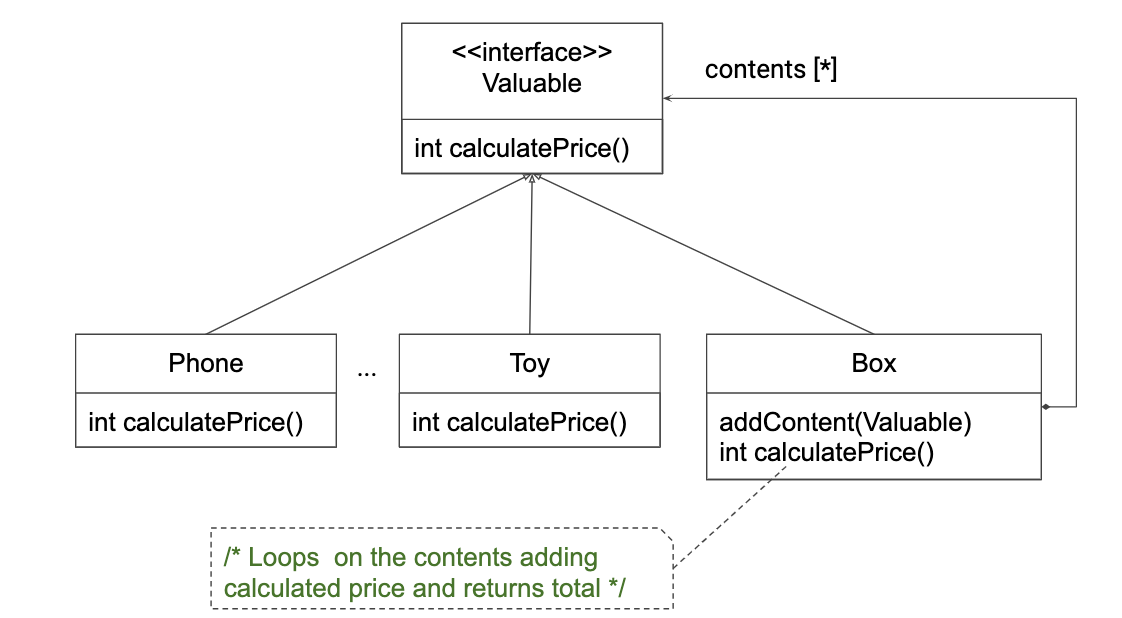

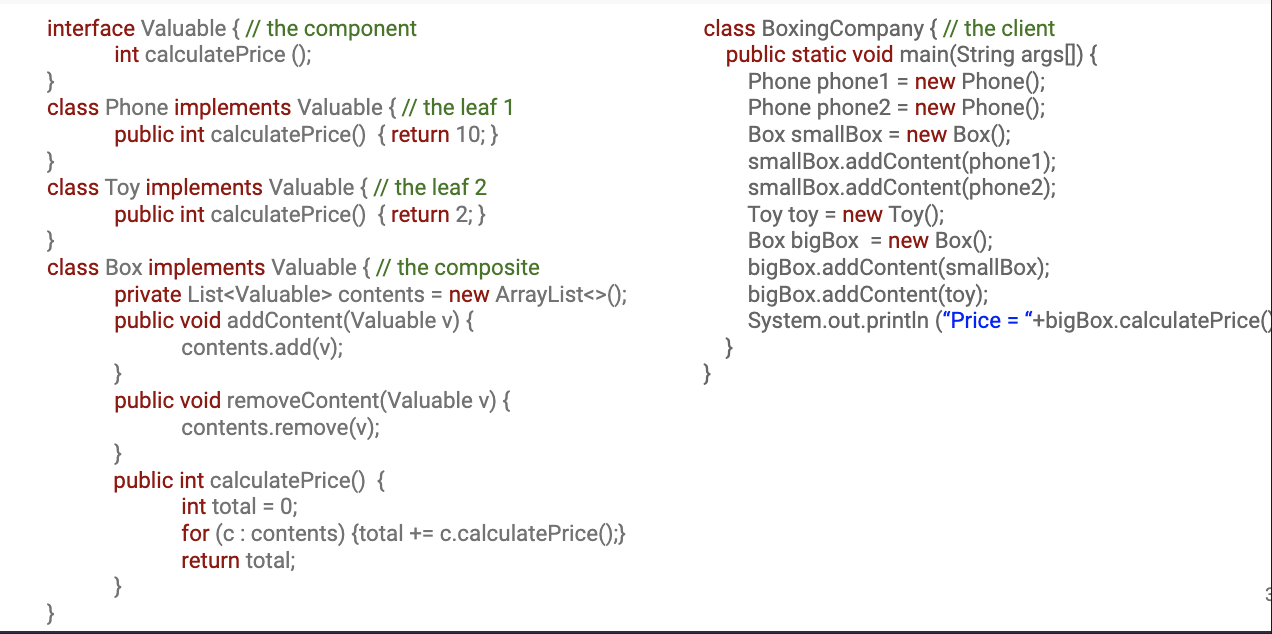

Composite Pattern

- a hierarchy of classes where higher order classes can contain lower order classes (usually tree structure)

- a composite object must implement the hierarchy structure as an individual object

- box example as a composite object

GoF Behavioral Patterns

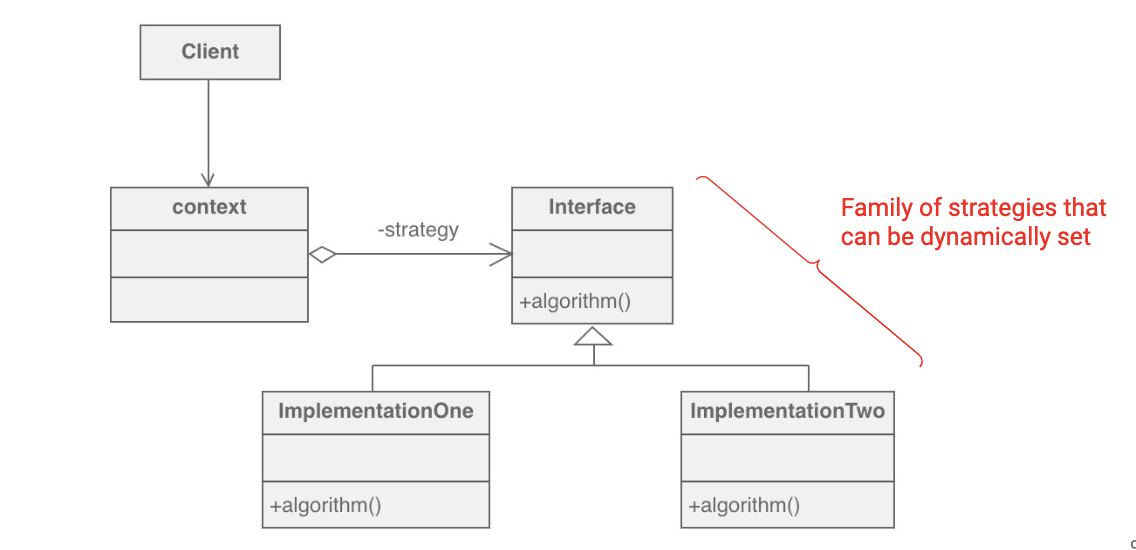

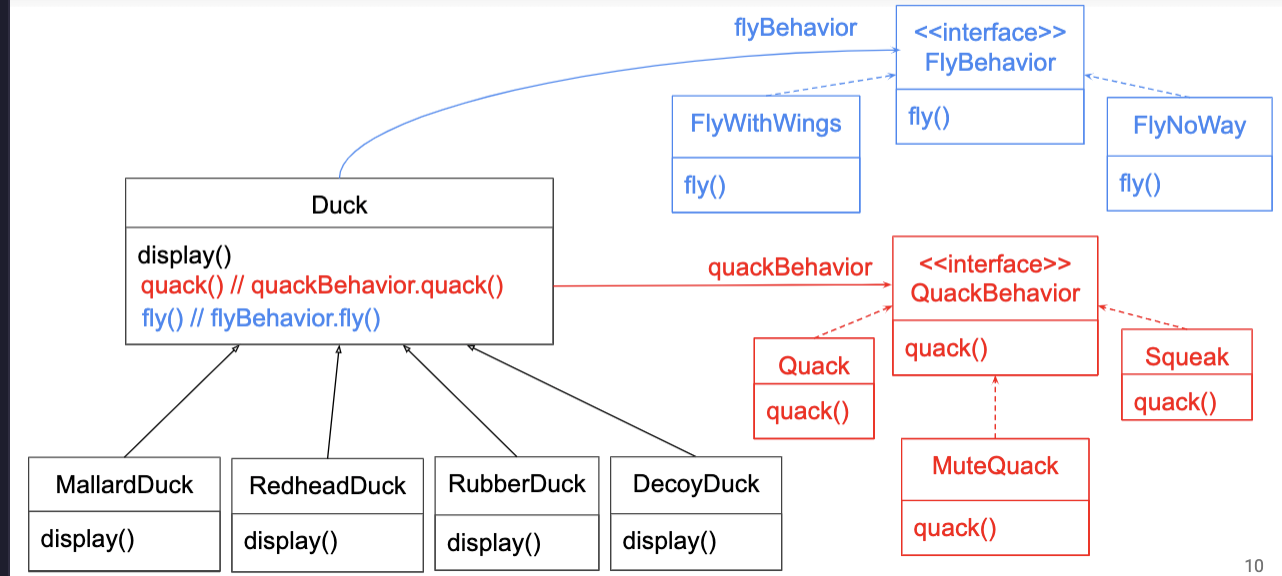

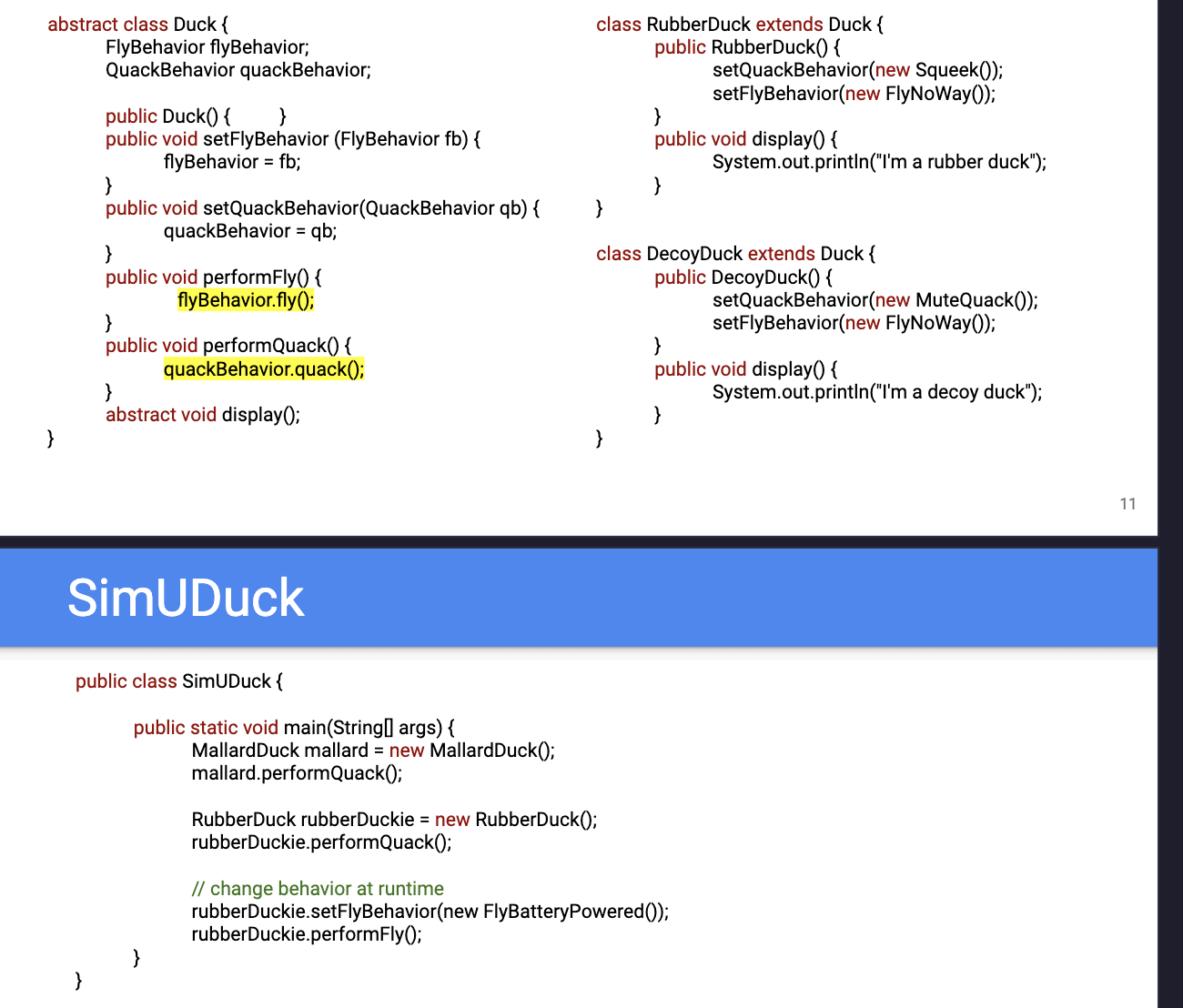

Strategy Pattern

- problem: class can do task in many ways at many times -> bloated and fragile -> apply strategy pattern to mitigate

- e.g. consider inheritance is not alwayss the best due to overriding many funcs in subclass, instead consider interface extension

Java Example

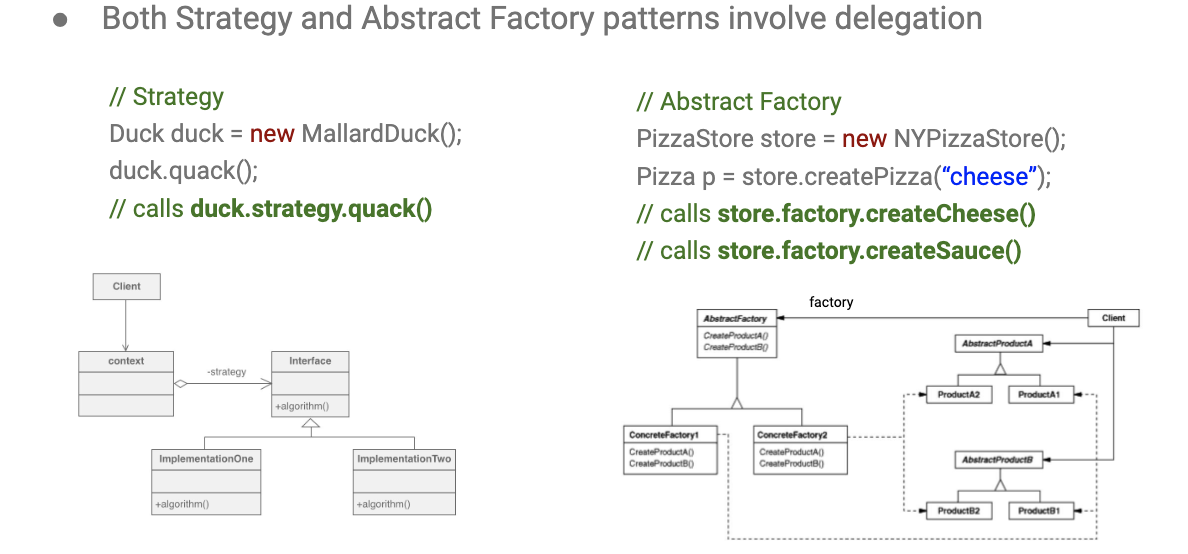

Strategy vs Abstract Factory

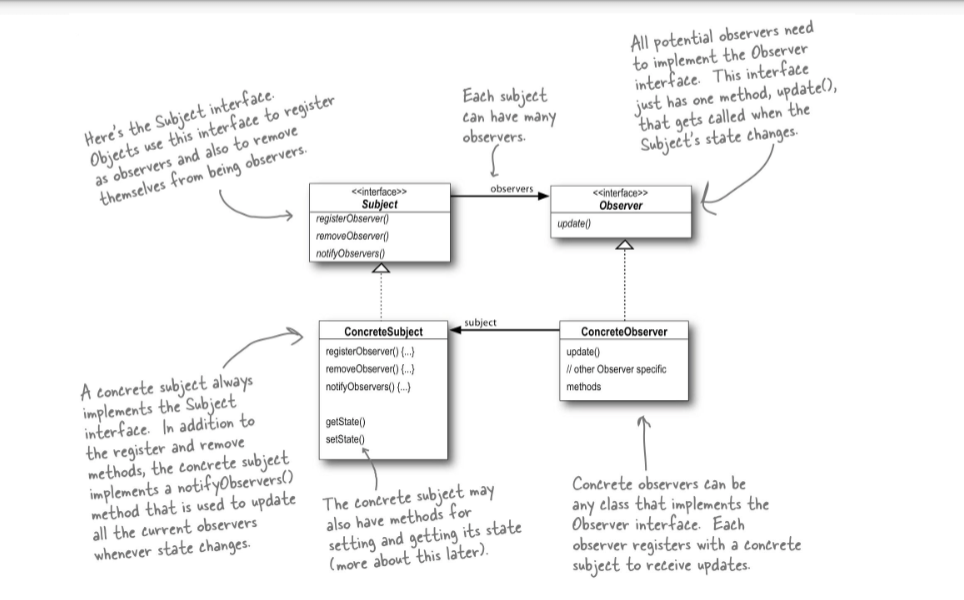

Observer Pattern

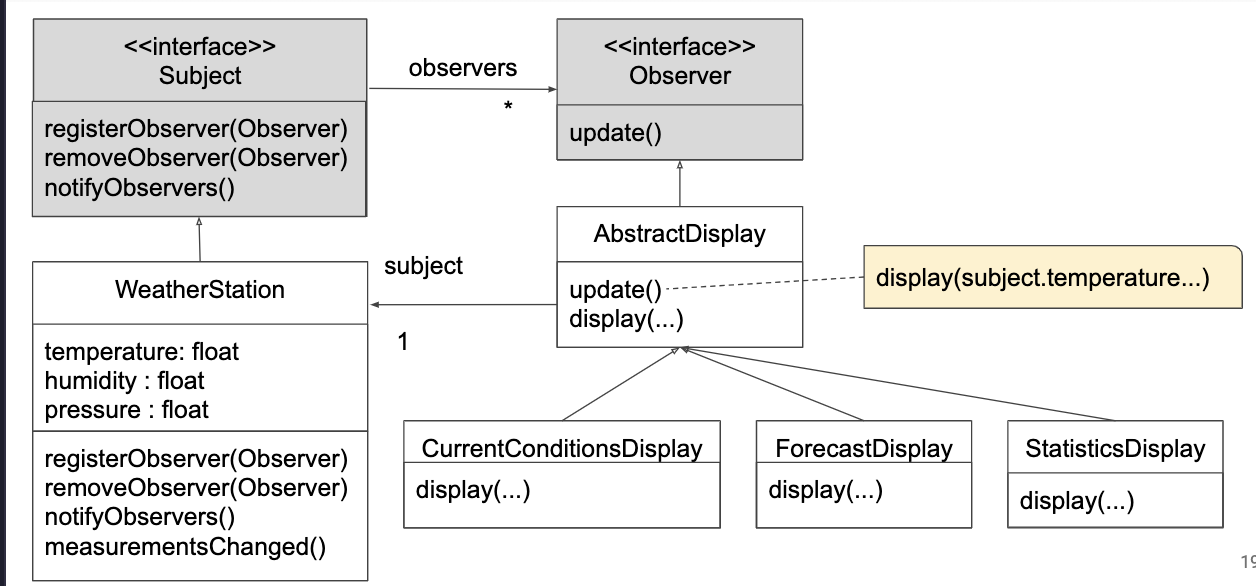

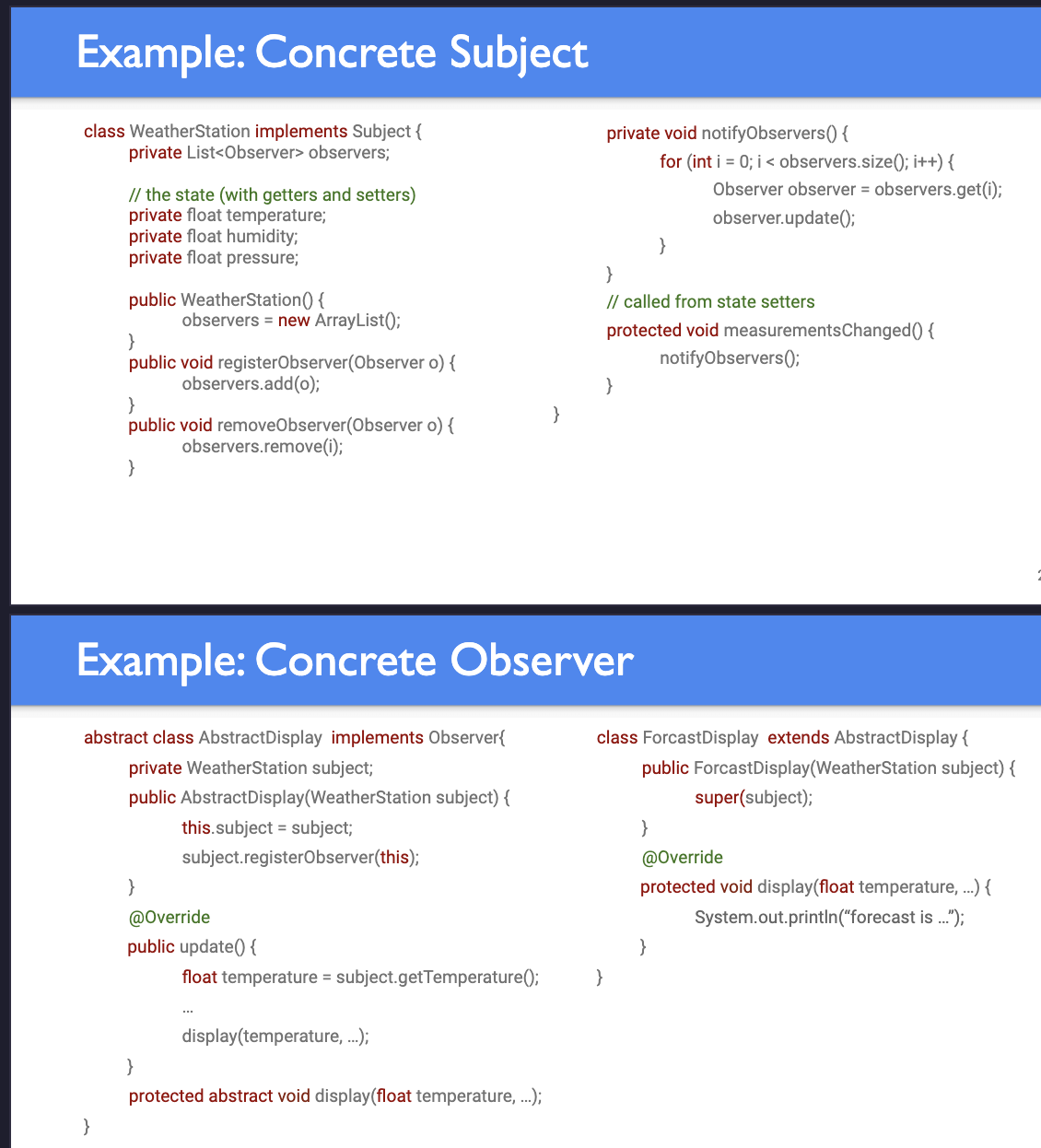

- problem: need to propagate state changes to all dependent objects

Weather Station Example

- core weather service must propagate new data to visual, api, displays

interface Subject { public void registerObserver(Observer o); public void removeObserver(Observer o); public void notifyObservers(); } interface Observer { public void update(); }

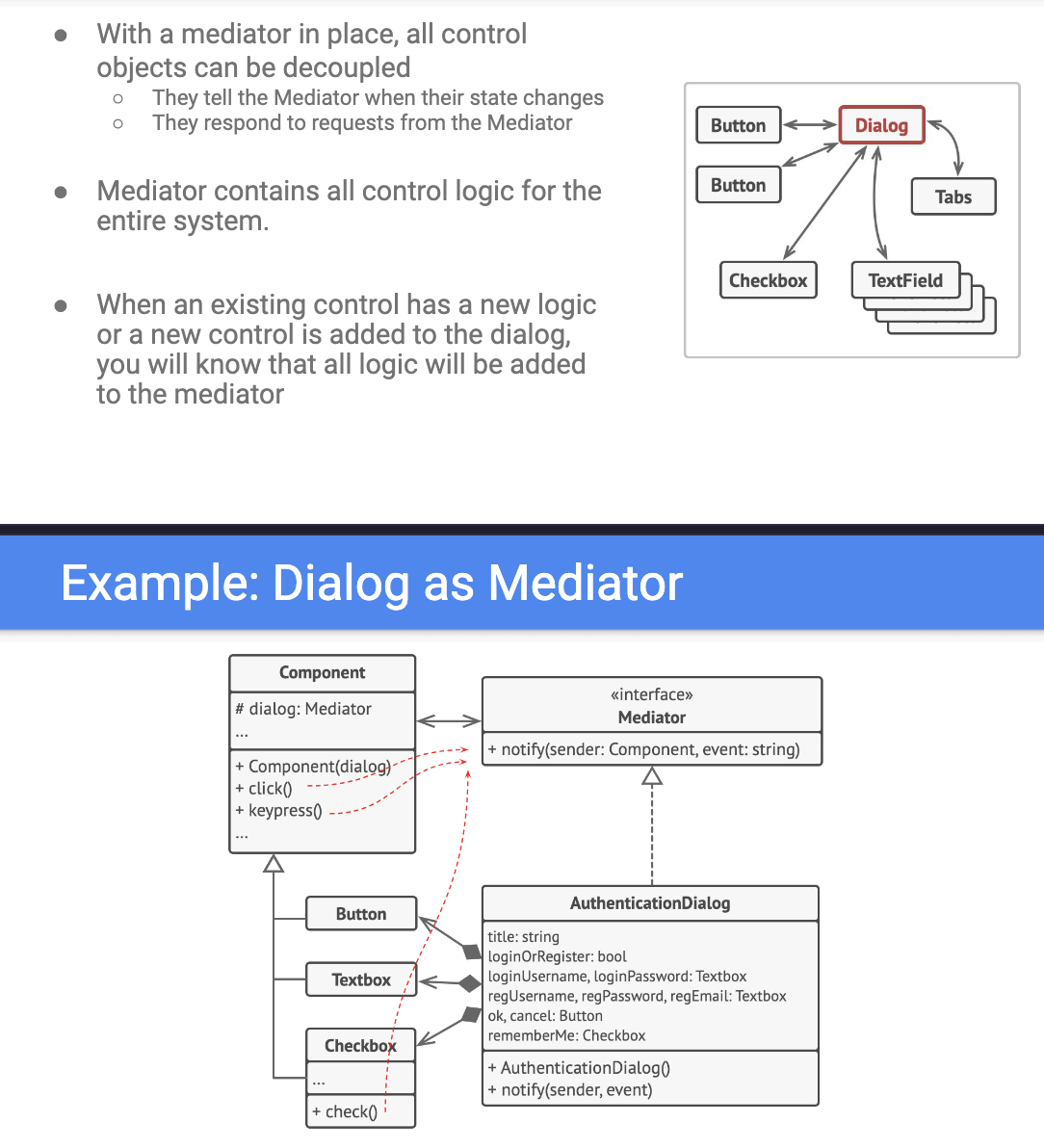

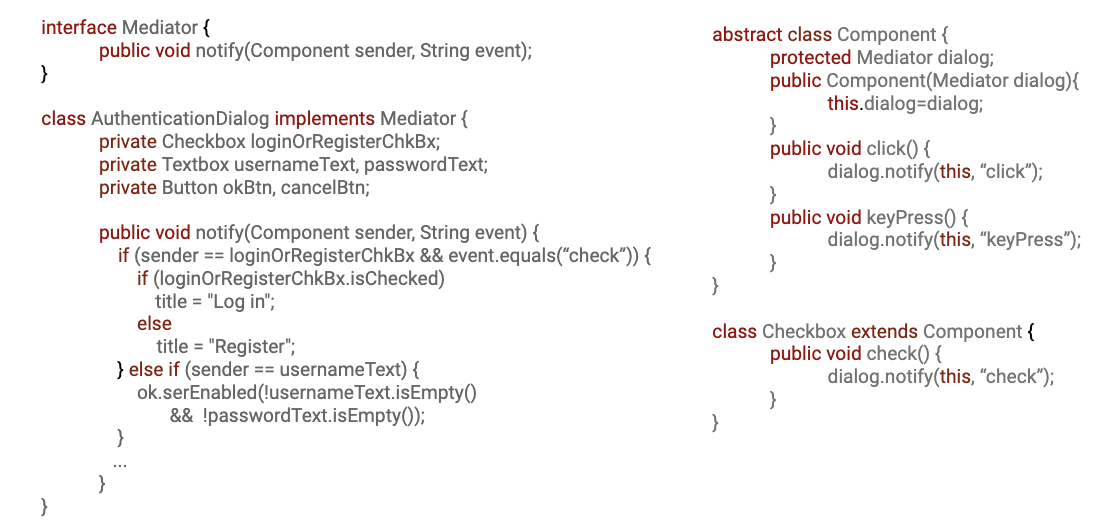

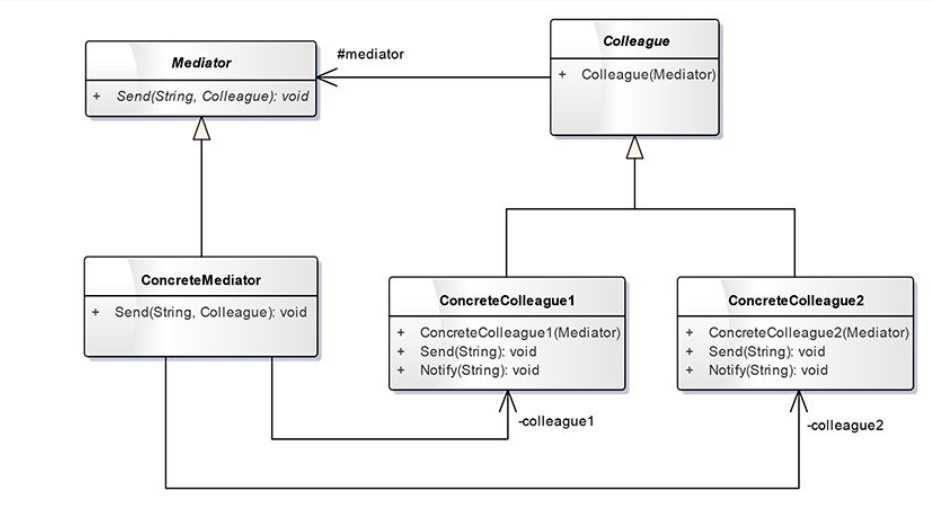

Mediator Pattern

- remove coupling between frequently interactive applications without having to change interactions

- pros:

- inc reusability of objects supported by Mediator by decoupling

- simplify maintenance by centralizing

- minimize diversity of messages sent between interacting services

- cons:

Mediator vs Observer

- mediator abstracts into one to many comms

- from possibly many comms endpoints to one mediator sends -> all dependencies

- observer abstracts service into many to many comms

- from one core service/data endpoint to abstracted dependencies

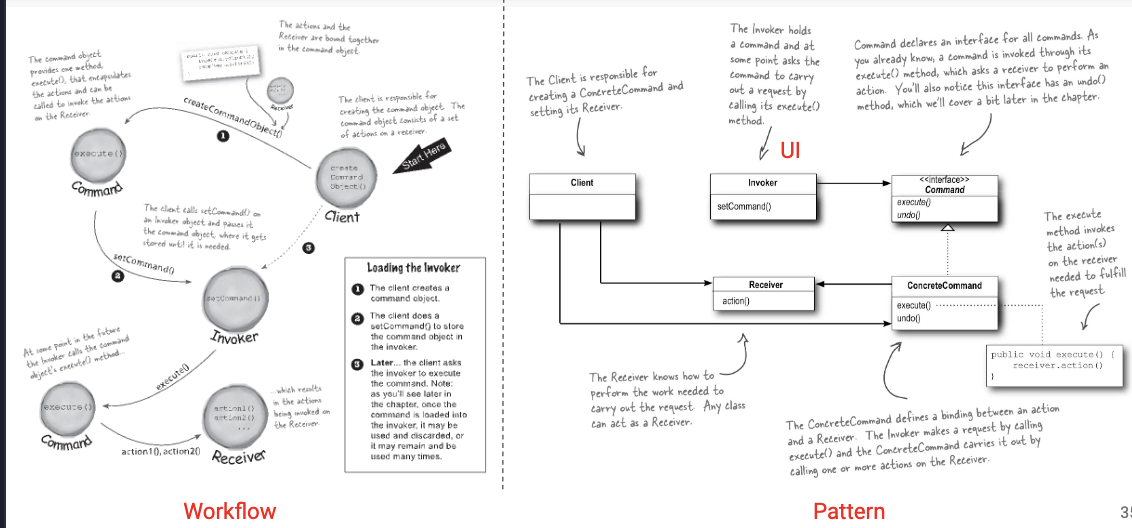

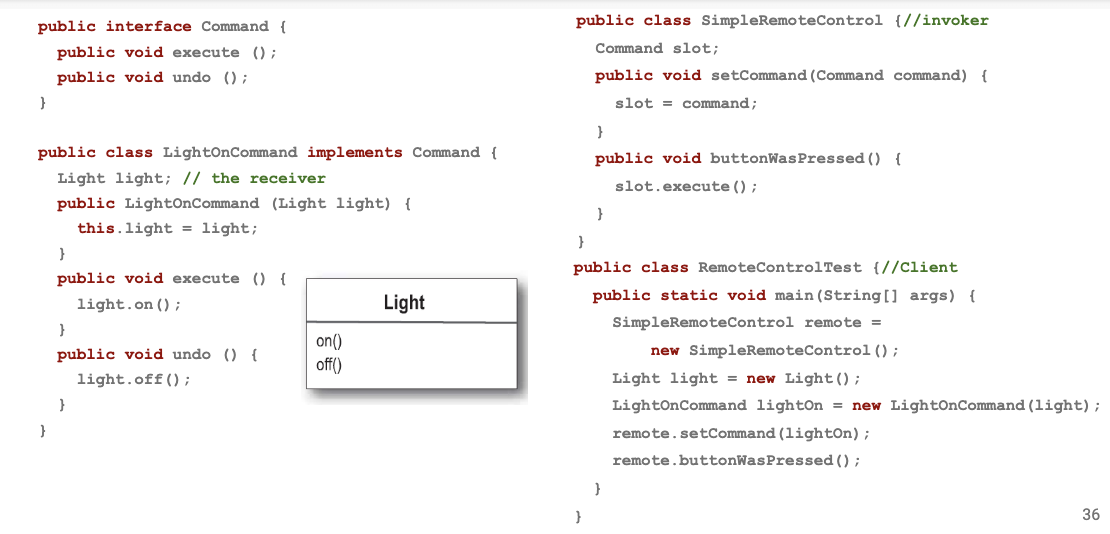

Command Pattern

- need to issue requests to objects without knowing the receiver or how request will be handle, e.g., remote control (circuits abstracted to commands on controller)

- possibly complicated by storing state as some functions may need undo/redo, some may not support - can’t just implement “execute” for all

- code example for remote control

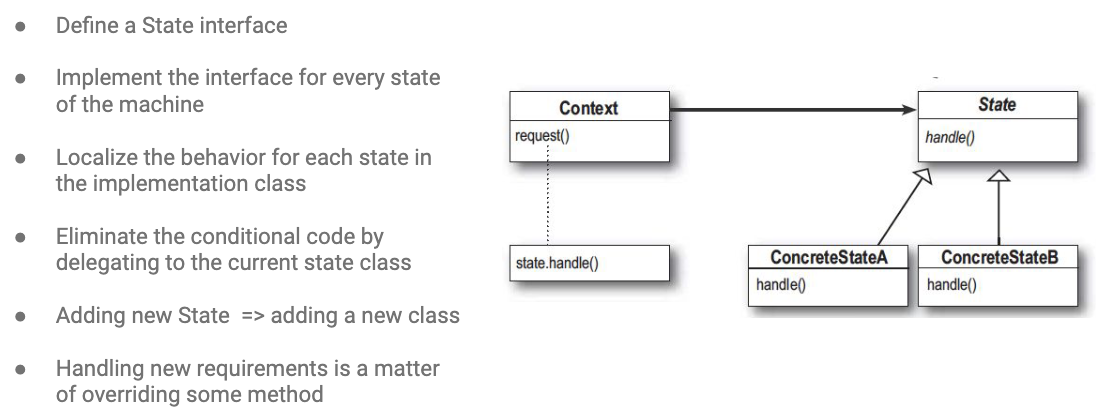

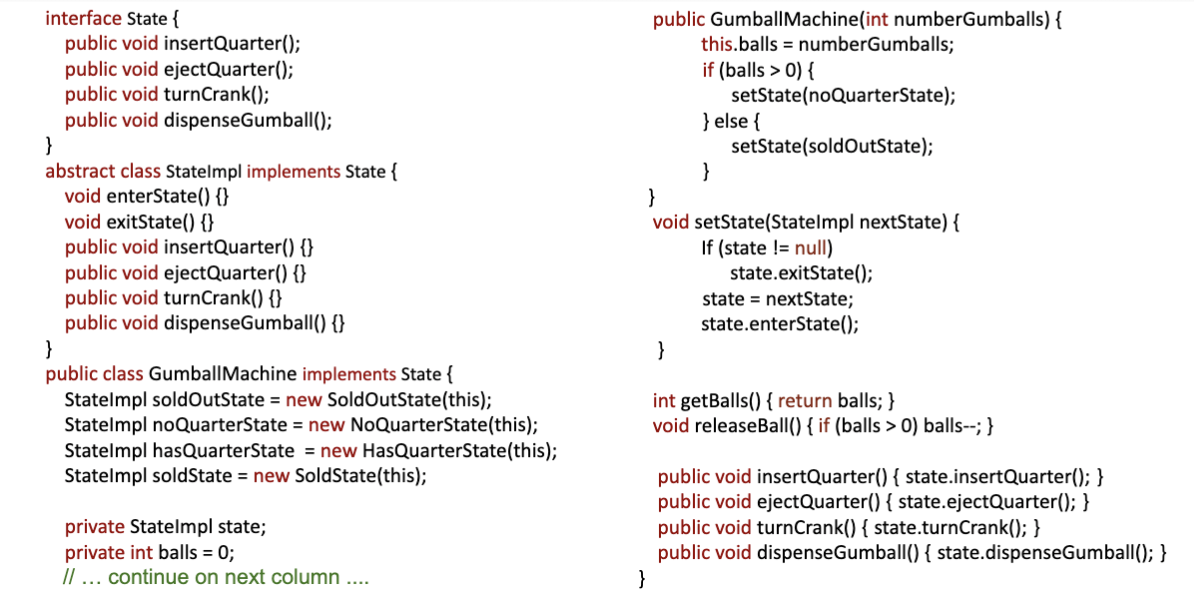

State Pattern

- when behavior is dependent on state e.g., gumball machine

- pros:

- encapsulates all state behavior into one object

- avoids state inconsistency

- cons:

- bulky code -> increases number of objects

- state interface is brittle, may require propagation to dependencies for new states